THE WORLD AS DREAM

An Excerpt from Chapter 1 of "The Waking Dream: Unlocking the Symbolic Language of Our Lives" (Quest Books, 1996)

To the magus, there exists no accidental happening . . . everything is established solidly by that law which the wise man discerns in happenings that appear accidental to the profane. The curve observed in the flight of birds, the barking of a dog, the shape of a cloud, are occult manifestations of that omnipotent = coordinator, the source of unity and harmony. Kurt Seligmann, Magic, Supernaturalism, and Religion

During a trip through the Southwest in 1982, I spent an afternoon with a Native American medicine man, a figure respected and feared by fellow villagers for his medicinal and magical knowledge. After talking for several hours about his practices and beliefs, he suggested we carry our conversation outside and take a walk along the edge of the village looking out over the desert.

As we made our way along the sandy pathway, he asked about my life and interests back home in the Midwest. I started telling him about a project I was scheduled to become involved in. Exactly at the moment I related my suspicions that this effort appeared to be taking a much different direction than I had originally intended, a bird conspicuously darted in front of us letting out a sharp cry, only to change direction abruptly and make a sharp right turn. Noting this event, my companion cheerfully remarked, "See! There you are! Like you thought, things are going to turn out quite differently than you originally planned." When I asked him to explain himself, he told me the signs around us indicated this. The winged apparition at the precise moment I spoke provided a message about what would transpire for me. He went on to say such messages are around us all the time, but nowadays we have forgotten how to read them. "We have lost the capacity to interpret the signs from nature," he said.

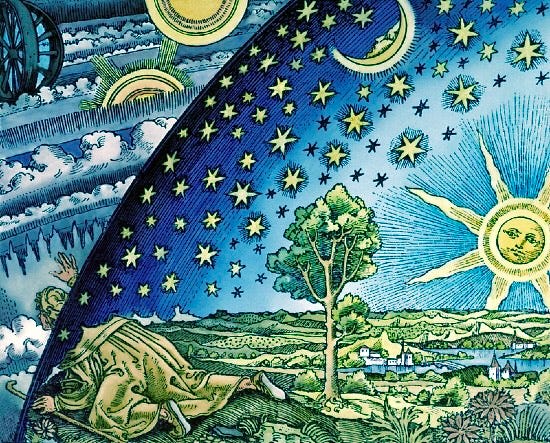

To the contemporary mind, the notion there might be messages or signs within random events seems strange, even absurd. Yet for millennia, such perceptions were commonplace in societies around the world. Whether we read stories of Chinese scribes seeking guidance by interpreting sticks thrown randomly on the ground, or hear tales of ancient Romans scrutinizing omens in the entrails of sacrificed animals on the eve of battle, or study accounts of Tibetan priests searching out candidates for the position of high Lama by gazing into a sacred lake, we find ourselves confronted with a way of viewing the world profoundly different from our own. As seen from this ancient perspective, reality is pregnant with hidden meanings and connections waiting to be unlocked by the discerning mind.

Symbolist thinking regards the world as a kind of language, with the people, animals, and events representing elements of a living vocabulary; a flower may be linked to a distant star, or an animal's movements entwined with the thoughts of a passing observer. Nowadays, we dismiss such notions as little more than remnants of a primitive age with a misguided predilection for confused categories and magical thinking. We tolerate that a dancer might have a pair of lucky shoes, but for most of us, the objects and random events of our daily life have no inherent meaning or significance.

But are such ideas only superstition, with no validity or importance? Or, can it be that in our wholesale rejection of the symbolist worldview, we overlook a level of insight hidden beneath the patent foolishness this way of looking at the world seems to imply?

It is curious, despite the rising tide of scientific and secular thought, that many of the greatest creative and philosophical minds of recent centuries have continued to find value in symbolist ideas. Consider Emerson's statement, "Every natural fact is a symbol of some spiritual fact." [1] In a well‑known essay, the German philosopher Schopenhauer reflects upon the curious design that underlies the apparent accidents of our lives, as if to suggest a deeper organizing principle beyond the range of conscious perception. [2] In a related vein, the philosopher and mathematician Gottfried Wilhelm von Leibniz developed a theory to explain how the outer events in our lives coincide with our inner development in a grand expression of "pre‑established harmony [3]; while his contemporary Isaac Newton privately entertained deeply occult notions concerning the subtler forces and laws that underlie the phenomena of nature. As economist John Maynard Keynes observed, Newton "saw the whole universe and all that is in it as a riddle, as a secret which could be read by applying pure thought to certain evidence, certain mystic clues which God . . . hid about the world to allow a sort of philosopher's treasure hunt to the esoteric brotherhood. [4]

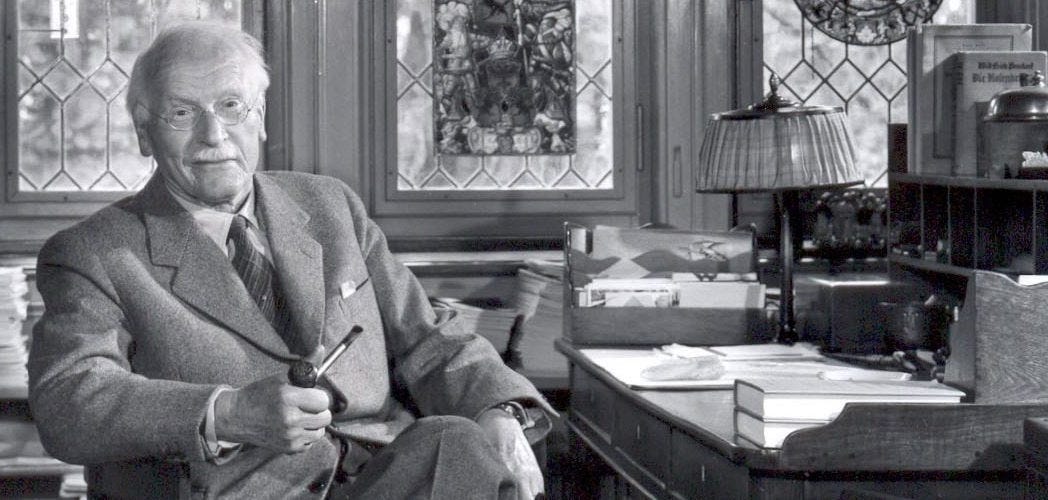

In more recent times, psychologist Carl Jung coined the term synchronicity to define the puzzling sense of design that lies behind coincidences in our lives; [5] while his Austrian forerunner in the study of coincidence Paul Kammerer used the term seriality to describe his own unique theories of this same phenomenon. On studying Kammerer's research concerning coincidences, Albert Einstein concluded it was "original and by no means absurd. "[6] And recently, a man regarded by millions around the world to be among the leading spiritual figures of our times, the Dalai Lama, openly professed a belief in omens and oracles. [7]

In the field of literature, we likewise find many of the greatest writers drawing inspiration from this same stream of thought. In his epic work Ulysses, Irish novelist James Joyce crafted a vision of reality underscoring both the archetypal undercurrents of ordinary experience as well as the intricately coincidental nature of events in our lives. In an article commemorating the centenary of Joyce's birth, Dan Tucker offered the following comments on Joyce's symbolist perspective:

There is something inside‑out about Joyce's books compared to other writers': messiness and jumble and horseplay out in the open, the shape buried deep. What at first looks like a hodgepodge or a joke turns out to be all interconnected, laced together with hundreds of tiny threads . . . insignificant scraps of memory and association. They keep popping up just often enough to imply some sort of design. Do you notice something about that comment? It applies to our own lives. Life is like Ulysses that way, full of haphazard, pointless events and coincidences, variations on silly themes. But every so often they hint at connectedness, structure, hidden meanings; often enough to keep us looking for those things. We don't want the things that happen to us to be meaningless‑a mere succession of events. And just by their shape and texture, Joyce's books keep telling us that they aren't meaningless. [8]

In his book Coincidance, Robert Anton Wilson cites the following dramatic example of synchronicity from Joyce's life. Joyce once made a trip to visit the grave site of a former romantic rival, Michael Bodkin, who had earlier courted Joyce's wife‑to‑be. Paralleling the events in Joyce's short story "The Dead," Bodkin died of pneumonia after singing love songs to his beloved in a rainstorm. On finding Bodkin's grave, Joyce was startled to discover the headstone immediately next to it bore the name "J. Joyce"‑an incident which, Wilson suggests, left Joyce with a lifelong preoccupation with synchronicity long before Jung had himself labeled this phenomenon. [9]

A continent away during an earlier century, the grandfather of modern literary symbolism, Herman Melville, composed Moby Dick, one of literature's most enduring and insightful testaments to the traditional symbolist worldview. Not only the White whale but every event and person in Melville's story operates on multiple levels, as he Writes, "Hark ye yet again‑the little lower layer. All visible objects, man, are but as pasteboard masks" (Chapter 36).

Symbolist thinking also captured the imagination of Goethe, Germany's greatest writer. In the closing lines of his life work, Faust, he declared, "All that is transitory is but a metaphor." Goethe too was intrigued by the sense of patterning which seemed to characterize many life events and speculated as to the possible source of this design. Aniela Jaffé writes:

In Goethe's view there exists an ordering power outside man, which resembles chance as much as providence, and which contracts time and expands space. He called it the ‘daemonic,’ and spoke of it as others speak of God. [10]

What intrigued these masters of philosophy, science, and literature? To begin to understand their fascination, we need to familiarize ourselves with the essential presuppositions which underlie the symbolist outlook.

A MEANINGFUL UNIVERSE

Those who believe that the world of being is governed by luck or chance and that it depends upon material causes are far removed from the divine and from the notion of the One. —Plotinus, Ennead VI.9

To step into the worldview of the man or woman for whom the universe is meaningful is to enter a way of thinking that views all events and phenomena as elements of a supremely ordered whole. Like the intricately arranged threads of a great novel or myth, so the elements of daily experience are seen as intimately interrelated, with no situation or event out of place, no development accidental. In this way, even a seemingly trivial occurrence may serve as an important key unlocking a greater pattern of meaning. The passage of a bird through the sky, the appearance of lightning at a critical moment, or the overhearing of a chance remark‑such things are significant to the degree they are perceived as interwoven within a greater tapestry of relationship. Unlocking their significance requires an ability to perceive holistically how an individual event or detail fits into a larger set of experiences and developments.

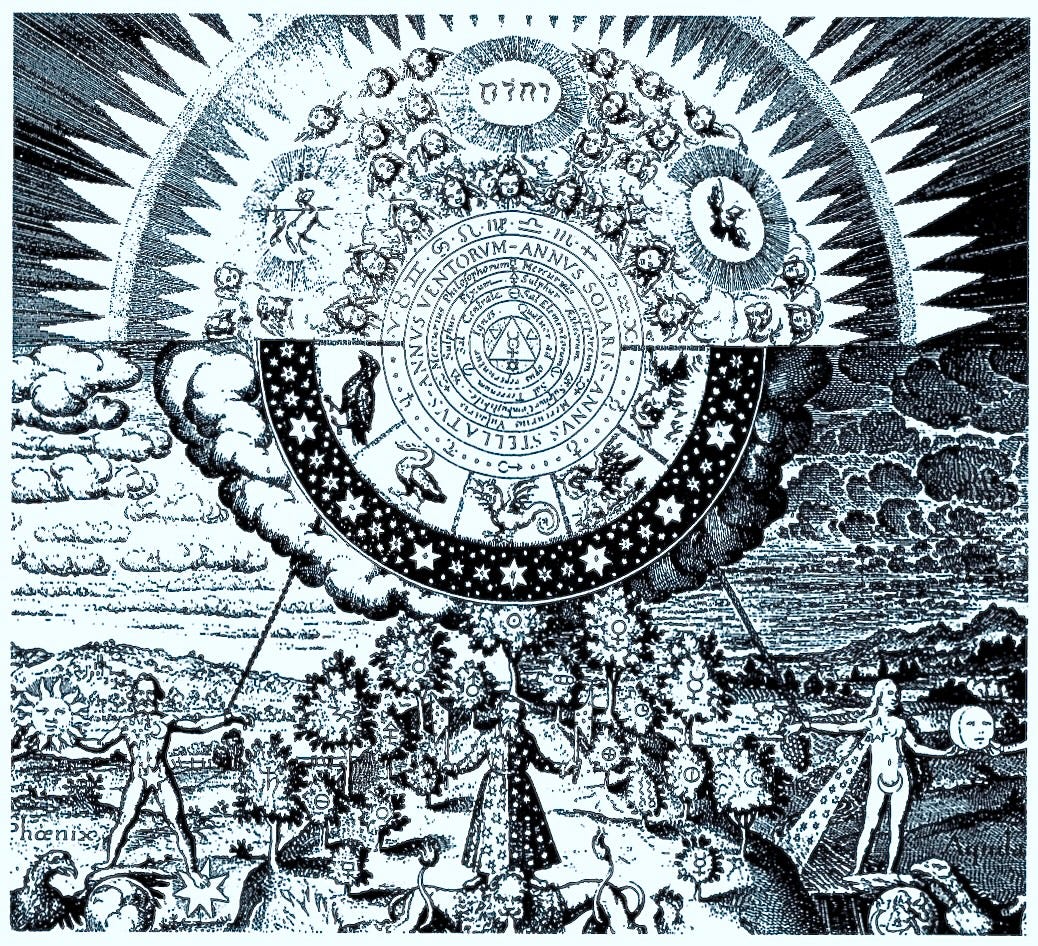

Underlying this view is a deep conviction that all events are themselves the manifestation of a greater, more fundamental ground of being. In contrast with the modern mechanistic viewpoint, which regards nature as an essentially physical phenomenon with no inherent meaning or consciousness, traditional symbolic thought perceives the world as suffused with mind, with all events and perceptible forms representing facets of a spiritual intelligence made visible. As the Swedish mystic and scientist Emmanuel Swedenborg commented in Heaven and Earth, "There is a correspondence of all things of heaven with all things of man." All things reflect the deeper ideas and esoteric principles of which they are a visible expression, or "signature," and can thus be deciphered for their higher significance.

For many cultures, this same idea found a more poetic expression in the belief that the world represents a kind of dream, similar in many respects to our fantasies during sleep. In Taoism, for example, there is a story of the man who dreamt one night he was a butterfly, only to discover upon waking he was a man. How could he be certain, he now wondered, whether he was a man who had dreamt he was a butterfly, or a butterfly who was now dreaming he was a man? As the Buddha said,

Thus shall ye think of all this fleeting world; A star at dawn, a bubble in a stream, A flash of lightning in a summer cloud, A flickering lamp, a phantom, and a dream.

For the symbolist, the recognition of the essentially dreamlike character of reality carries with it a series of far‑reaching implications. For instance, if experience is a kind of dream with its own symbolic dimension of meaningfulness, then it must also be possible to interpret it like a dream. Events and circumstances unfolding outwardly are reflections of developments occurring on deeper levels of our own consciousness. As in the myths and sagas of antiquity in which the important developments and beings encountered along the hero's or heroine's journey are ultimately recognized as guides and initiators in the unfoldment of a greater spiritual quest, so in our own life the people, events, and creatures encountered can be seen as messengers bearing important clues into our own unfolding inner processes.

In this way, a randomly observed auto accident may hold a clue to understanding some inner conflict or problem; an unexpected gift of flowers may reveal a subtle shift of fortunes; or a job application lost in the mail or other recurring obstacle in the pursuit of a goal may be interpreted as reflecting a deeper lesson needing to be learned.

Read as dream symbols, ordinary occurrences yield depths of information and teaching completely unsuspected by the untrained observer.

NOTES:

1. Ralph Waldo Emerson, "Nature," from The Writings of Ralph Waldo Emerson (New York: Modern Library, 1940), 15.

2. Arthur Schopenhauer, quoted by Joseph Campbell in The Masks of God, Vol. IV:

Creative Mythology (New York: Viking Press, 1968), 193-194.

3. For a concise summary of Leibniz's theory of "pre-established harmony," see Ira Progoff, Jung, Synchronicity, and Human Destiny (New York: Dell Books, 1973), 67-76.

4. John Maynard Keynes, Newton the Man," in Newton Tercentenary Celebrations (Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 1947), 27-29.

5. Carl Jung, "Synchronicity: An Acausal Connecting Principle," in Collected Works, vol. 8 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1969).

6. Quoted by Arthur Koestler in The Roots of Coincidence New York: Random House, 1972), 87.

7. Concerning omens, the Dalai Lama has remarked: "We (all the Buddhist schools] believe in oracles, omens, interpretations of dreams, reincarnation. But these beliefs, which for us are certainties, are not something we try to impose on others in any way." From The Dalai Lama in conversation with Jean-Claude Carriere," in Violence and Compassion: Dialogues on the World Today (New York: Doubleday, 1996), 20.

8. "Ringing Down the Curtain on Joyce's 100th Year," Book World, Chicago Tribune, Dec. 26, 1982.

9. Robert Anton Wilson, Coincidance (Phoenix, AZ: New Falcon Press, 1991).

10. Aniela Jaffé, The Myth of Meaning (New York: Putnam, 1971), 153.

Ray Grasse is a writer, astrologer, and photographer based in the American Midwest. He graduated from the Art Institute of Chicago with a double major in filmmaking and painting, and studied with teachers in the Kriya Yoga and Zen traditions. His websites are www.raygrasse.com and www.raygrassephotography.com.