Legends of the Fall

[Excerpted from So, What Am I Doing Here, Anyway?]

“Why should a man’s mind have been thrown into such close, sad, sensational, inexplicable relations with such a precarious object as his body?”

—Thomas Hardy

Towards the end of his life, Goswami Kriyananda (of Chicago) made a series of deeply occult statements about the human condition, one of which in particular stood out for me:

“The Earth is the only planet in this solar system where the people have fallen from the astral world (of that planet) down onto the surface of the planet. On all the other planets, people are there, but they’re not on the surface of those planets; they are in what is called the air realm, which we call the astral realm. So if you went to those planets you would not see people on the surfaces there.”

Lots to unpack there, friends. It’s an idea mentioned by other mystics and occultists as well, directly or indirectly, including Rudolf Steiner and Edgar Cayce, among others. When I posted Kriyananda’s comment on social media not long ago, it elicited a surprising number of responses, of which the key one was probably this:

What would cause us to ‘fall’ from the astral down into bodies on a planet in the first place?

It’s not a simple question, of course, but it’s a critical one, since it touches on one of the most fundamental mysteries of all—namely, why are we here?

One possibility suggested by various mystics and spiritual traditions through history might be called the “allurement” theory. Simply stated, this suggests that we’re gradually enticed by embodied life here on planet Earth by the various pleasures of this planet—particularly (though not exclusively) food and sex.

After all, look at the Earth compared to the other planetary bodies of our system. What is there to entice beings up on subtler levels to come down physically to the surface of a planet like Venus, say, with its scorching 867 ̊ F temperatures? Or Mercury, with its barren metallic features? Or Uranus with its icy cold atmospheres?

But Earth – ahhh! This most Taurean of all planets represents a veritable playground of sensual pleasures and “earthly delights.” It’s a supremely beautiful world with a seemingly boundless smorgasbord of sights, sounds, tastes, and textures to appeal to the physical senses, ranging from the fragrance of flowers and flavors of exotic fruits to the luxurious settings of tropical islands and the sexual ecstasies offered by a loving partner.

“Garden of Eden” by Rousseau

One might well ask, wouldn’t those experiences be just as enjoyable in their astral form as in the physical? Apparently not. As I heard Kriyananda once explain it, there is something about the sheer “tangibility” of experiences like sex and food that is more viscerally satisfying when experienced through bodies than via their more ethereal counterparts on the astral, or in dream states. A disembodied spirit may well draw close to appreciating such mortal experiences while hovering around our planet’s surface, taking in the sights and sounds spread out before it—yet it just isn’t the same.

As a result, we can imagine a scenario where a spirit plays with entering into the bodies of certain animals, plants, hominids, or even plants—all in order to “taste” those phenomena. (Imagine becoming a sequoia tree, even if just for a moment!) Though this may initially take the form of momentary experiments or earthly “vacations,” the spirit may eventually find itself sucked in and stuck here, addicted to those worldly sensations, as it were—and in the process, forgetting its true home and original nature.

In one form or another, this is a theme that echoes throughout various ancient myths and legends—including, of course, the Biblical tale of Adam and Eve in the Garden. (Notice, incidentally, how it’s specifically the taste of a fruit that leads to their fall.) But I’ll be coming back to that story shortly.

I find it fascinating that we’ve seen a similar motif re-emerging in contemporary culture in recent decades, but framed in the guise of science fiction. Though we find touches of this in the writings of authors like Stanislaw Lem, Philip K. Dick, and John Varley, one particularly high-profile, popular expression was the 1982 film Tron. This Disney-produced movie features a central character (played by Jeff Bridges) who goes from being a game player and developer to getting sucked into the virtual reality of his computer world, where he finds himself contending with the complexities of his digital reality. In stories like these, the computer becomes a metaphor for embodied existence itself; it’s “the Fall,” all right, but in a more hi-tech setting.

The message is clear: we may think we’re just playing a “game,” yet it’s one we can easily get lost in—and in the end, forget who and where we are.

A Gnostic Reading of the Biblical “Fall”

I want to return now to the Old Testament tale of Eden, to offer up a more nuanced interpretation of “the Fall,” since I think it can shed valuable light on another aspect of what that myth means. To be clear, I don’t intend for any of what follows to be taken literally, as an actual account of real events that took place in ancient times. Though I think there’s some truth to it, it’s not meant as a point-by-point correlation. Rather, I see the story as a way to mythologically convey certain truths about consciousness, particularly those involving spiritual awakening.

To begin with, imagine that you are God and you’ve given birth to this extraordinary creation. Yet you are not alone; there are other beings in existence, but of lesser awareness and power than yourself. (Whether you choose to see these other beings as created by God, or as fully independent beings or “mini-gods” distinct from the creator, but having entered into forms created by God, as mystics like Shelly Trimmer and some Gnostics believe, isn’t as important for our purposes here. For the sake of our discussion, I’ll be taking the latter view here—that of Adam and Eve as independent god-beings.)

Imagine that in your benevolence, as God, you allow those other beings in existence to enter into your creation, your “cosmic dream,’ so that they can benefit from the multifarious lessons and gifts your creation offers. At the astral level where these beings have settled in, perhaps in the astral realms above Earth, it’s a generally blissful existence. In this scenario, God is almost akin to a protective mother who nurtures her children, who reside safe and sound within the cosmic womb of God’s sacred creation. [1]

There’s just one downside, however.

Having entered this protective Edenic state, those beings have yet to really awaken to their own inherent God-natures. Like proverbial infants in the womb, these beings are protected, nurtured, and quite comfortable in their seemingly “perfect” existence; there isn’t even any need to make decisions or think for themselves yet.

But as a result, they’re also relatively unaware, relatively unawakened. There’s nothing inherently wrong with that, any more than there’s anything wrong with an infant remaining happy and blissfully unaware in the womb. But at some point, remaining in that Edenic condition becomes decidedly unhelpful, like a child refusing to actually grow up and think for itself.

To say it a little differently, in that primordial Edenic state those beings are simply operating on “God’s programs,” not on their own. Akin to the way a child is guided along a path determined by its parents, so it is with these beings who reside cocooned in the warm embrace of God’s creation. For them to grow, they need to start initiating their own lives, taking charge of their own destinies—to start stepping outside of the Garden, as it were.

So how does change like that come about?

Well, once again suppose you’re God. How do you encourage those beings nestled within your creation to start waking up and breaking free from your cosmic programming, to start developing their own free will and consciousness? You can’t force anyone to awaken and grow; that’s tantamount to interference. For it to really “stick,” that awakening has to come from within. So how do you ignite that spark, and do so without forcing it on those beings?

There is a way, actually, but it involves a kind of “trick,” a sort of reverse psychology. You see, by offering Adam and Eve a choice that’s virtually guaranteed to make them decide for themselves, in a way that contrasts markedly with Godly directives and programming, you help to light that spark of their own free will.

So, you say to Adam and Eve, “I have this magnificent garden, and you are free to enjoy it—but whatever you do, don’t eat or touch that fruit from the tree in the middle of the garden! I’m warning you, stay far, far away from that tree, or you’re in big trouble!”

Framing it this way, of course, essentially ensures that they will want to taste that fruit—much in the same way that telling someone not to think of pink elephants will ensure they’ll soon be thinking of nothing but. And they will do so completely of their own free will.

And therein lies the beginning of the so-called “Fall,” when the mini-gods engage in their very first act of free will, one that was

truly initiated from within and not enforced from without. They can now start to exert free will, because you’ve given them a choice—because without choice, there is no such thing as free will.

Adam and Eve with the serpent (from Michelangelo’s mural in the Sistine Chapel).

And surprisingly enough, their ally in this process was the serpent in the garden. How is that? The serpent advises them to go ahead and eat of the fruit, at which point they will become as gods! Esoterically, the serpent symbolizes the divine energy within each of us, the inner God-voice, and is associated with the spinal energies—the proverbial “tree of life” inside us. The serpent was actually speaking truth to Adam and Eve by directing them to go against the God without and awaken the God-nature within. In fact, the serpent and God were close allies in this awakening process, as if working hand-in-hand.

But there is a catch. Yes, this act of seeming defiance was the beginning of spiritual awakening—the inauguration of free will and the first act of self-determination—yet this same act also sets into motion the domino effect of karma.

You see, there is no such thing as “karma” without conscious choice or free will being involved. Even our secular judicial system thinks along these lines—i.e., gauging the consequences of actions by how old or mature the accused offender is. We don’t impose the same punishment on a seven-year old for stealing something that we would on a 30-year old for the same crime. That’s because we know there isn’t full awareness or free will involved yet; the child is simply acting out of their biological programming, blindly. Similarly, we don’t judge an animal as “evil” when doing something deadly, because we know there’s no real free will or conscious intention involved there either. They, too, are acting out of pure instinct, deep hardwiring.

In that same way, karma doesn’t start accumulating until we begin awakening, until we start employing our free will and consciousness. As described in the Biblical story of the Fall, Adam and Eve now enter into a new era of suffering, desire, and decision-making, at which point we’re told they take on “clothes”—that is, bodies. As a result of this cumulative karma, they become denser in vibration, weighed down by increasingly greater amounts of karma—and thus begins the descent from the astral realms above planet Earth down into embodiment on the surface of the planet.

The Return

But that is hardly the end of the story.

On its surface, this story may seem like a downward spiral from perfection to imperfection, a tragic fall into a realm of sin, suffering, and struggle. But that’s only a microscopic view of a much greater narrative, the first stage in a multi-act drama. Perhaps the best exposition of that broader story I’ve come across is in the ancient tale The Hymn of the Pearl, which is a passage from the apocryphal Acts of Thomas. To my mind, this story provides some crucial clues into the meaning of our sojourn on this lonely planet, and here is how I summed it up (slightly reworded here) in my book When the Stars Align:

It tells the tale of a boy, the “son of the king of kings,” who is sent down into Egypt to retrieve a pearl from a mysterious serpent. But while on that mission, he is seduced by Egypt and its ways, and consequently forgets his home country and family. A letter is then sent to him from the king to remind him of his background and royal heritage, at which point he remembers his mission, retrieves the pearl, and returns home.

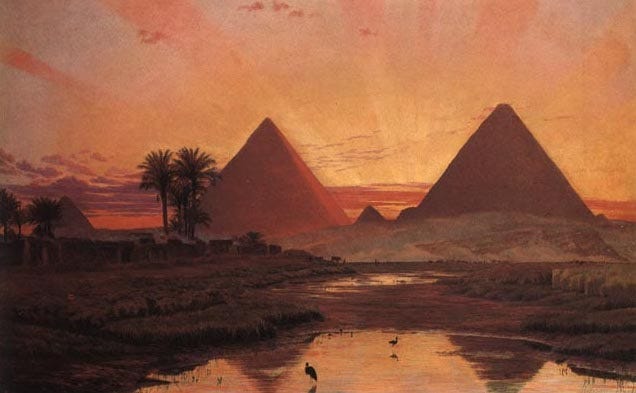

by Thomas Seddon,1856.

In terms of symbolism, “Egypt” in that tale represents sensory, worldly existence itself, in which we can likewise easily become lost—and will forever remain lost until we receive that message from our Higher Self reminding us to complete our mission and return home again. One of the key points of the story is that our sojourn in this realm is not a waste of time, nor is it meaningless; there is a treasure to be gained from enduring this mortal existence, which is symbolized by the pearl.

That choice of symbols (as opposed to, say, a treasure chest, golden crown, or even a butterfly) is significant, when you consider that a pearl’s beauty arises from the interaction of a rough irritant (like a grain of sand) with the surrounding oyster.

In a somewhat similar way, it is through our soul’s “rough” interaction with this world and its hardships that something of great beauty arises. That’s not to say that one should seek out hardships or suffering, because even the mystics say the wisest option is to learn without it, when possible. But as the Buddha himself pointed out, that’s not always possible; suffering is, to some extent, part and parcel of mortal existence, with its rounds of life and death, beginnings and endings.[2]

In short, the so-called “Fall” is actually a key part of the overall awakening, with our time spent in the incarnational cycle being integrally connected to the emergence of that beautiful pearl. [3] As the mythologist Martin Shaw said, “To never leave Eden is to stay surrounded by spirit, but remain uninitiated by soul.” [4] Yes, this Earth is a “rough” realm, where we necessarily encounter resistance and obstacles at every turn; our patience is tested, our dreams delayed or even denied, and we’re forced to deal with difficult people and temptations of every kind. Most painful of all, we have to contend with our own limitations and flaws.

But in the process of working on these outer challenges and inner flaws, we’re being “initiated by soul”—and something of great worth and beauty emerges from that process. Resistance is key to this: by pushing up against life’s obstacles, by developing self-discipline to control our consciousness and resist the lures of countless desires or impulses, we develop inner mastery and thereby gain a newfound sense of direction. In Homer’s epic Odyssey, Ulysses must contend with an assortment of temptations and challenges on his way back from the chaos of war, but in the end finally prevails and reunites with his beloved in Ithaca—his own personal “Eden.”

It is because of our sojourns through the mortal realms that we also learn to develop sensitivity, empathy, and compassion—qualities far harder to come by up in idyllic Eden. [5] In the end, it’s through the young man’s journey down into “Egypt” that his soul thereby becomes refined, his nature is transformed.

Our own story began when we first cast ourselves out of Eden through that original spark of awakening, but in the end we return there with new eyes—at which point we see that it is actually an inner Eden we are coming home to. As the poet T.S. Elliot said, “We shall not cease from exploration, and the end of all our exploring will be to arrive where we started and know the place for the first time.”[6]

He may as well have been speaking about Eden.

NOTES:

1. There are different variants on the Gnostic perspective, some of which are more malevolent in nature, where God is viewed as a more sinister being out to entrap us, while some other variants are more benevolent in nature, where God is regarded in a comparatively more positive—or at least less malevolent—light (these generally associated with the “Valentinian” school). What I’ve been drawing on here, inspired primarily by the teachings of Shelly Trimmer, clearly falls into the latter camp.

2. As cited in my essay “Suffering and Soul Making on the Mean Streets of Planet Earth, in chapter 12 of When the Stars Align.

3. The idea that the “Fall” may actually be an integral part of our evolutionary growth has naturally led many even within the mainstream church to regard humanity’s original transgression in the Garden in a surprisingly different light. Mythologist Joseph Campbell often spoke about the Latin phrase employed in church liturgy, “O Felix Culpa”—which translates as “O Happy Fault!,” though sometimes paraphrased as “O necessary sin of Adam!” Necessary? This curious phrase speaks to the paradox of how Adam’s “sin” in the Garden actually made possible the eventual salvation of humanity by Jesus, and was thus to be celebrated, not lamented.

4. Quoted from Martin Shaw’s online essay, “The Fall and the Underworld,” https://martinshaw.substack.com/p/the-fall-and-the- underworld.

5. Here again, see my essay “Suffering and Soul Making on the Mean Streets of Planet Earth,” in When the Stars Align.

6. T.S. Eliot, from “Little Gidding,” Four Quartets (Gardners Books; Main edition, April 30, 2001).

Ray Grasse is a writer, astrologer, and photographer based in the American Midwest. He is author of ten books, most recently In the Company of Gods. His websites are www.raygrasse.com and www.raygrassephotography.com.